The See-Feel-Listen Method That Decodes Any Fabric Texture

By Max Calder | 19 December 2025 | 17 mins read

Table of contents

Table of Contents

Ever spend hours tweaking a digital fabric, only for it to look flat and unconvincing in your final render? We've all been there. This guide moves beyond a simple list of names to teach you a hands-on, systematic method for identifying any fabric texture, so you can finally build digital materials that look and behave like the real thing. This isn't just textile trivia; it's the foundational skill that lets you stop guessing at software presets and start making informed decisions, translating the physical world into your digital workflow to create truly believable garments.

Start with the fundamentals: What creates texture?

Ever download a fabric file that looked great as a thumbnail but felt flat and lifeless in your render? We’ve all been there. The problem isn’t always the software; it’s that we’re missing the foundational knowledge of what makes fabric feel like fabric. Texture isn’t just a surface-level detail; it’s the result of deliberate choices made long before a garment is ever designed.

Think of it this way: you can’t build a realistic digital asset without understanding its physical blueprint. Let's unpack the core components that create the vast world of textile textures.

Unpack the building blocks: Weave, knit, and finish

At its core, a fabric’s texture begins with its construction. How the threads are put together is the primary driver of its feel, drape, and character. There are two main families here: wovens and knits.

Woven fabrics are built on a grid system, like a basket. They consist of warp threads (running lengthwise) and weft threads (running crosswise) interlacing at right angles. The pattern of this interlacing is called the weave, and it’s responsible for the fabric's stability and many of its surface characteristics.

- Plain weave: The simplest form. Each weft thread goes over one warp thread and under the next. This creates a strong, stable fabric with a smooth, slightly matte surface. Think quilting cotton, poplin, or chiffon. It’s a reliable workhorse.

- Twill weave: This is where you see those distinct diagonal lines. The weft thread floats over two or more warp threads, then under one, with the pattern shifting on each row. This structure makes fabrics like denim, chino, and gabardine incredibly durable and allows them to hide stains well. It has a more textured, interesting surface than a plain weave.

- Satin weave: Known for its incredible sheen and fluid drape. Here, the weft thread floats over multiple warp threads (four or more) with minimal interlacing points. This creates a super-smooth, reflective surface on one side. It’s what gives satin and sateen their luxurious feel, but it can be more prone to snagging.

Knit fabrics, on the other hand, are made from a single, continuous yarn looped together, kind of like a chain-link fence. This structure is what gives knits their signature stretch. If you look closely at a t-shirt, you’ll see tiny, interlocking braids. This inherent elasticity is a key identifier. Jersey, rib knit, and fleece are all common examples.

But construction is only part of the story. Finishing processes are manufacturing techniques applied after the fabric is woven or knit to alter its final texture.

- Napping/Brushing: A process where the fabric is passed over abrasive rollers to lift fiber ends from the surface, creating a soft, fuzzy feel. This is how you get flannel and brushed cotton.

- Embossing: Uses heated rollers to press a pattern into the fabric, creating a raised, three-dimensional effect. Think of embossed velvet.

- Calendering: High-pressure rollers create a super-smooth, high-sheen surface on fabrics like chintz.

Understanding these fabric manufacturing processes helps you decode why a fabric looks and feels the way it does, a crucial insight when you’re trying to replicate it digitally.

Understand how fiber choice dictates feel (Natural vs. Synthetic)

If the weave or knit is the skeleton, the fiber is the flesh. The raw material used has a massive impact on the final textile surface characteristics. Every fiber has an inherent personality.

Natural fibers come from plants or animals, and they bring their organic origins with them.

- Cotton: It's the king of comfort for a reason. The fibers are soft, breathable, and absorbent. Think of the crisp feel of a new poplin shirt or the soft comfort of an old t-shirt. Its texture is familiar and versatile.

- Wool: Known for its warmth, which comes from the natural crimp in the fibers that traps air. It can range from the scratchy, rustic feel of Shetland wool to the buttery softness of merino. It has a natural elasticity and often a slightly fuzzy or textured hand.

- Silk: The epitome of luxury. Produced by silkworms, this protein fiber is incredibly smooth, strong, and lustrous. Its texture is defined by its frictionless glide and beautiful, fluid drape.

- Linen: Made from the flax plant, linen is known for its crisp, cool feel and visible texture, including characteristic slubs (small, thick bumps in the yarn). It wrinkles easily, but that’s part of its charm.

Synthetic fibers are engineered, and their textures are designed for performance.

- Polyester: A true chameleon. It can be engineered to feel like silk, cotton, or wool. On its own, it’s known for being durable, wrinkle-resistant, and having a slightly slick or plastic-y feel. It doesn't breathe like natural fibers.

- Nylon: Strong, stretchy, and smooth. It was originally developed as a silk substitute and is often used in performance wear and hosiery for its slick surface and excellent recovery.

- Rayon/Viscose: These are semi-synthetics made from regenerated cellulose (wood pulp). They were designed to mimic the feel and drape of silk, offering a soft hand and fluid movement at a lower cost.

So, why does a wool sweater feel completely different from an acrylic one, even if they have the same knit? It’s the fiber. Wool fibers have a complex, scaled structure that breathes and insulates; acrylic is a smooth, plastic-like fiber that traps heat and moisture. When you’re selecting fabrics, always start with the fiber. It sets the baseline for everything else.

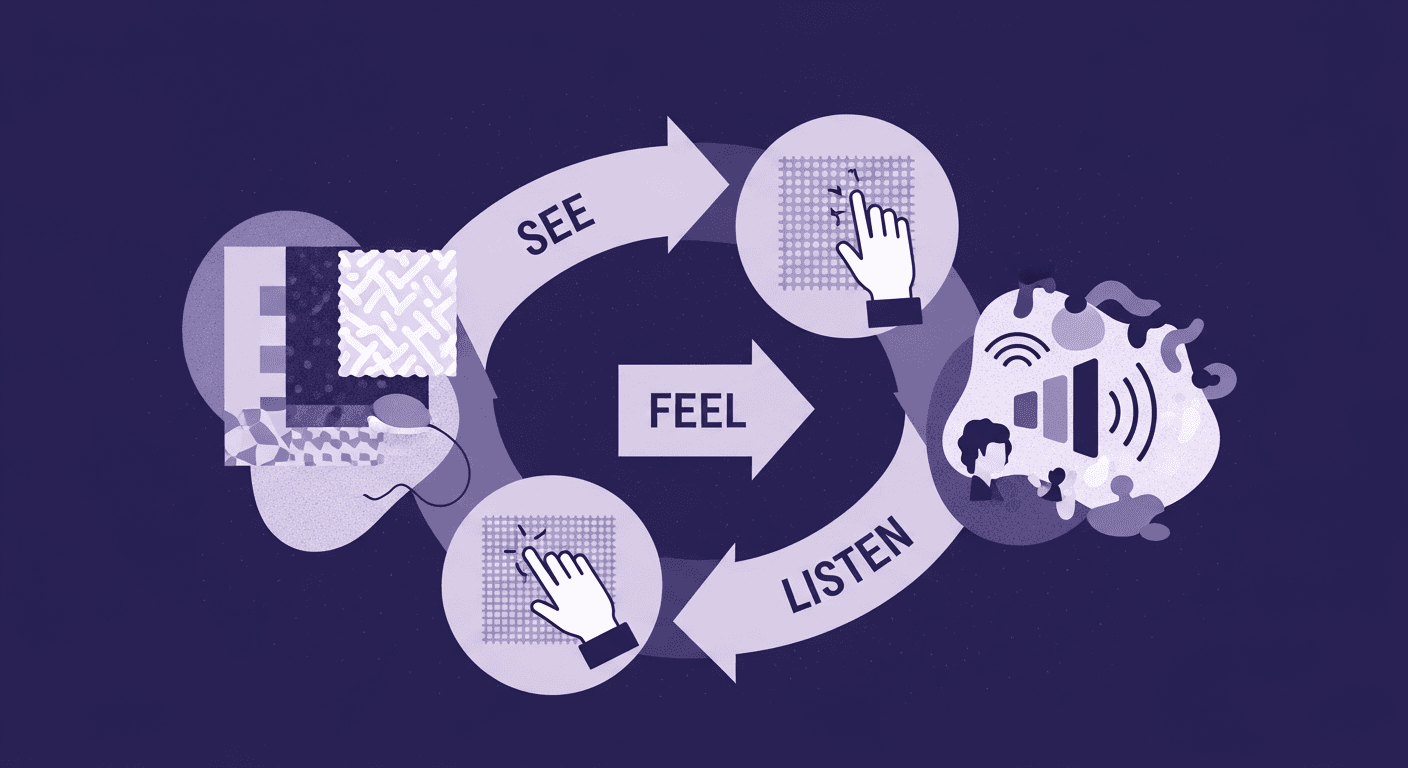

Develop your sensory method to identify textile textures

You don’t need a microscope or a lab to become an expert in fabric identification. You just need to train your senses. Most people just grab a fabric and make a snap judgment. We’re going to build a repeatable, three-step method that will give you a deep understanding of any textile you pick up. This systematic approach is how you move from guessing to knowing, a skill that will directly translate into more believable digital creations.

Step 1: The visual scan for surface patterns

Before you even touch the fabric, your eyes can give you a ton of information. Hold the fabric up to the light. Look at it from an angle. This is your initial data-gathering phase.

Here’s what you’re looking for:

- Sheen vs. Matte: Is there a bright, reflective shine like satin, or is the surface dull and absorbent like cotton flannel? Sheen points to long fiber floats (like a satin weave) or specific fibers like silk and polyester.

- Visible weave/Knit: Can you see the construction? Look for the diagonal lines of a twill (denim), the grid-like pattern of a plain weave (canvas), or the tiny V-shapes of a jersey knit (t-shirt). A clear, visible structure tells you a lot about its stability.

- Surface elements: Are there raised components? Look for the vertical ridges of corduroy, the looped pile of terry cloth, or the fuzzy surface of fleece. These are immediate, obvious clues.

- Irregularities: Does the fabric have intentional imperfections? The slubs in linen or shantung silk are a key part of their identity. These aren’t flaws; they’re texture.

This visual scan allows you to form a hypothesis. Okay, I see a high sheen and no visible weave, so I’m thinking satin. Now, let’s see if the touch test confirms it.

Step 2: The 3-part touch test for fabric texture identification

Now it’s time to engage your hands. This isn’t just about feeling if something is soft. We’re breaking it down into three distinct actions to gather specific data about the fabric’s properties.

- The surface glide: This is the most intuitive test. Run your hand lightly across the fabric surface. Don’t press down. What do you feel? Is it perfectly smooth and cool like silk charmeuse? Is it slick and synthetic-feeling like nylon? Do you feel the fuzzy, raised fibers of brushed cotton? Or is it rough and rustic, like a heavy linen or burlap? This test tells you about the fiber type and the finishing process.

- The drape & fold: This is mission-critical for 3D designers. How a fabric hangs under its own weight is its drape. Pick up a corner of the fabric and let it hang. Does it fall in soft, fluid cones like chiffon, or does it hold its shape with stiff, architectural folds like taffeta or canvas? Then, crease it between your fingers. Does it create a sharp, crisp fold (like organza) or a soft, rolling one (like jersey)? A fabric’s drape reveals its density, stiffness, and the interplay between its fiber and construction.

- The stretch & recovery: This is the definitive test to distinguish between a woven and a knit. Gently pull the fabric along its width (weft) and then its length (warp). Woven fabrics typically have very little give, maybe a tiny bit on the bias (diagonal). Knits, by their very nature, will have significant stretch, especially crosswise. Now, let it go. Does it snap back to its original shape immediately? That’s good recovery, typical of fabrics with spandex or high-quality knits. Or does it sag a bit? This simple test tells you about the fabric’s underlying structure and performance.

Step 3: Listen to the fabric

This might sound strange, but it’s an old-school technique that pros use. The sound a fabric makes when you handle it can be a surprisingly accurate identifier. It’s called its hand or rustle.

Crumple a piece of the fabric near your ear. What do you hear?

- A crisp, papery rustle is characteristic of stiff, tightly woven fabrics like taffeta, organdy, or some synthetics like nylon ripstop. This sound is often called scroop.

- A soft, muted swish suggests a lightweight, fluid fabric like chiffon or silk charmeuse.

- Total silence is also a clue. A heavy wool, fleece, or soft jersey knit will make almost no sound at all. They absorb sound, just as they absorb light.

This auditory feedback adds another layer of data, helping you distinguish between two fabrics that might feel similar but are constructed differently.

Build your digital and physical texture library

Knowledge is only useful when it’s organized. As you practice identifying fabrics, you need a system to document your findings. The goal isn’t just to name fabrics, it’s to build a personal library of textures that you can reference for your digital work. This is how you bridge the gap between the physical and digital worlds.

How to document and categorize fabric texture types

Start building a physical swatch book. You can get cheap fabric swatches online or from your local fabric store. For each one, create an entry.

Your system shouldn't be a random list of names. Instead, group your fabrics by their properties and feel. This is far more useful for a designer. You’re not thinking, “I need a fabric called crepe de chine.” You’re thinking, “I need something with a soft drape and a slightly pebbly texture.”

Here's a sample categorization system:

- Structured & crisp: Fabrics that hold their shape. (Taffeta, Organza, Denim, Canvas)

- Soft & fluid: Fabrics with beautiful drape and movement. (Silk Charmeuse, Chiffon, Rayon Challis, Viscose)

- Soft & cozy: Fabrics with a raised, comfortable surface. (Flannel, Fleece, Brushed Cotton, Terry Cloth)

- Rough & rustic: Fabrics with a noticeable, organic texture. (Linen, Burlap, Tweed, Raw Silk)

- Smooth & sleek: Fabrics with a clean, flat surface. (Poplin, Sateen, Nylon, Polyester Taffeta)

For each swatch, jot down your sensory notes using our method:

- Visual: High sheen, visible twill weave.

- Touch: Smooth glide, stiff drape, no stretch.

- Sound: Quiet.

- Fiber/Weave guess: Cotton, Twill Weave.

- Name: Denim.

Taking high-resolution photos of your swatches under different lighting conditions is also a great idea. This physical library will become your single source of truth.

Translate physical textures into digital assets

Now, here’s the magic. This detailed documentation is your cheat sheet for creating hyper-realistic digital fabrics in software like CLO3D. You’re no longer just guessing at the presets. You’re making informed decisions based on real-world physics.

Map your physical understanding directly to the digital parameters:

- Your Drape & Fold notes translate directly to the Weight, Bending, and Shear settings. A stiff fabric like canvas needs higher bending values, while a fluid silk needs very low ones.

- Your Stretch & Recovery test informs the Stretch and Buckling properties. Did it stretch a lot crosswise but not lengthwise? Adjust the Stretch-Weft and Stretch-Warp values accordingly.

- The Surface Glide gives you clues for the Friction setting, which affects how the fabric interacts with itself and the avatar.

When you use your detailed notes to search for or create digital fabric files, you can be far more precise. Instead of searching for red fabric, you can search for a lightweight satin with high sheen and fluid drape. This practice of grounding your digital work in physical reality will elevate your renders from good enough to indistinguishable from a photo. It's how you build a powerful, accurate, and unique digital fabric library that sets your work apart.

Put your texture knowledge into practice

Theory is great, but a method is only useful when you apply it. Let’s walk through a few common fabrics using the see, feel, and listen framework. This is how you internalize the process and build muscle memory.

Identify these common fabric textures using your new method

Let’s put three distinct fabrics to the test.

Example 1: Denim

- Step 1 (See): The most obvious visual cue is the distinct diagonal ribbing of the twill weave. You'll also notice that the surface is often a mix of blue and white threads, a result of the warp yarns being dyed indigo while the weft yarns are left white. It has a matte finish with very little to no sheen.

- Step 2 (Feel): For the surface glide, it feels sturdy, strong, and slightly rough. It's not a smooth ride. For drape and fold, it’s stiff and structured. It holds its shape and creates hard creases rather than soft folds. On the stretch test, traditional denim has almost no give. You can feel the tightly woven structure resisting your pull.

- Step 3 (Listen): It’s a quiet fabric. When handled, it produces a low, muffled sound due to its thickness and cotton content.

- Conclusion: The visible twill weave, rugged feel, and lack of stretch are dead giveaways for denim.

Example 2: Corduroy

- Step 1 (See): Instantly recognizable by its parallel cords or wales. These can be very fine (pinwale) or thick and chunky (wide-wale). The surface has a soft, velvety pile that catches the light, giving it a subtle sheen.

- Step 2 (Feel): The surface glide is unique; running your hand with the wales is smooth and soft, while going against them provides more resistance. It’s a very tactile, three-dimensional feel. The drape is typically stiff and structured, more so than denim. And for stretch, like denim, it has virtually none because it’s a woven fabric.

- Step 3 (Listen): It creates a very soft, low rustle when the wales rub against each other. It’s a quiet, comforting sound.

- Conclusion: The visible, touchable wales are the primary identifier for corduroy.

Example 3: Satin

- Step 1 (See): The number one clue is the high, lustrous sheen on one side and the dull, flat finish on the other. You won’t see a discernible weave pattern on the shiny side because of the long fiber floats.

- Step 2 (Feel): The surface glide is incredibly smooth, cool to the touch, and slippery. Your hand moves across it with almost zero friction. The drape is the opposite of denim or corduroy; it’s highly fluid and hangs in soft, elegant folds. It feels light. The stretch test reveals very little give, confirming it's a woven fabric (unless it has elastane blended in).

- Step 3 (Listen): When handled, it produces a very soft, quiet swish or hiss. It's a delicate sound that matches its delicate feel.

- Conclusion: The combination of high sheen on one side and a slippery, fluid hand makes it unmistakably satin.

Troubleshoot common identification mistakes

As your skills develop, you'll run into trickier situations where two fabrics seem almost identical. This is where nuanced observation becomes key. Distinguishing between similar fabric textures is what separates an amateur from a pro.

How to tell lawn from voile?

Both are lightweight, plain-weave cottons, perfect for summer clothing. They can feel very similar. The key difference is in their finish and density.

- Lawn is typically crisper and more opaque. It has a smooth, soft feel but holds a bit of body.

- Voile is sheerer, lighter, and has a harder twist in the yarn, which gives it a slightly wiry, crisp feel. Hold it up to the light; if you can see through it clearly, it’s likely voile.

How to tell Brushed Cotton from Flannel?

This is a tough one, as both are woven fabrics (usually cotton) that have been napped to create a soft, fuzzy surface. The lines can be blurry, and sometimes the terms are used interchangeably.

- Flannel is typically defined by a looser weave and is napped on one or both sides. The napping is often heavier, obscuring the underlying weave pattern. It feels thicker and cozier.

- Brushed cotton is often a more tightly woven fabric, like a twill or poplin, that has been lightly brushed to give it a soft surface. You can often still see the underlying weave more clearly than with flannel. It might feel a bit lighter and less fluffy than a true flannel.

Your new superpower? Thinking in texture

So, let’s bring it all back to that frustrating moment we started with: the flat, lifeless digital fabric. The gap between what you see in your head and what you get on screen.

After this, you should see that gap for what it is, not a software problem, but a knowledge problem. And it’s one you now have a repeatable method to solve. This was never about memorizing a list of fabric names. It’s about learning to decode the physical blueprint of a material so you can rebuild it with confidence in the digital world.

That swatch library you’re about to build? It’s not just a collection of scraps. It’s your new secret weapon. It’s your cheat sheet for translating the real world into software parameters, turning your notes on drape, feel, and stretch directly into data that works.

The next time you start a project, you won’t be guessing. You won’t be endlessly tweaking a generic preset, hoping to get lucky. You’ll be making intentional, informed decisions that get you to a photorealistic result faster. You’ll finally have a workflow that bridges the physical and digital divide.

You’ve got the method. Now go build something that feels real.

Max Calder

Max Calder is a creative technologist at Texturly. He specializes in material workflows, lighting, and rendering, but what drives him is enhancing creative workflows using technology. Whether he's writing about shader logic or exploring the art behind great textures, Max brings a thoughtful, hands-on perspective shaped by years in the industry. His favorite kind of learning? Collaborative, curious, and always rooted in real-world projects.

Latest Blogs

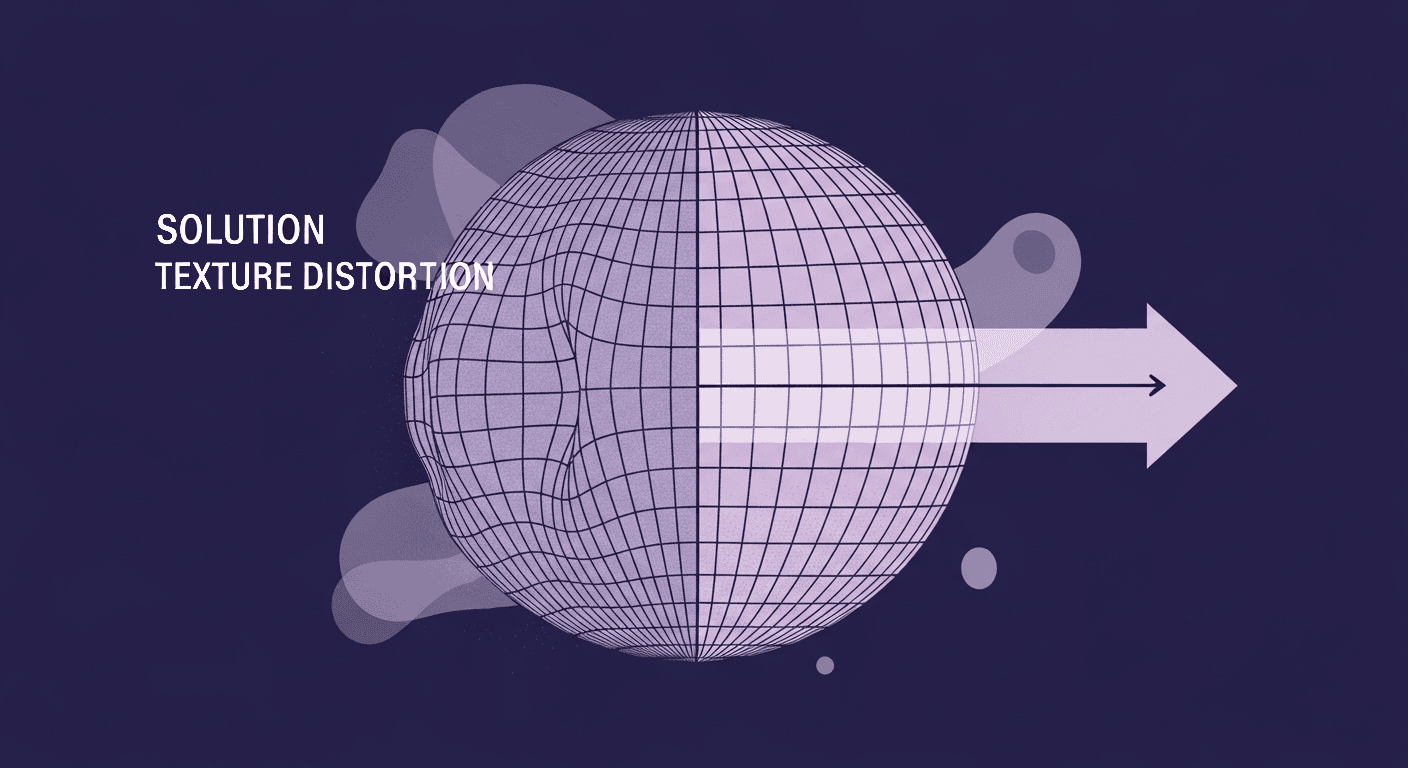

The Polar Pinch Problem: How VR Artists Solve Texture Distortion

Texture creation

PBR mapping

Max Calder

Dec 24, 2025

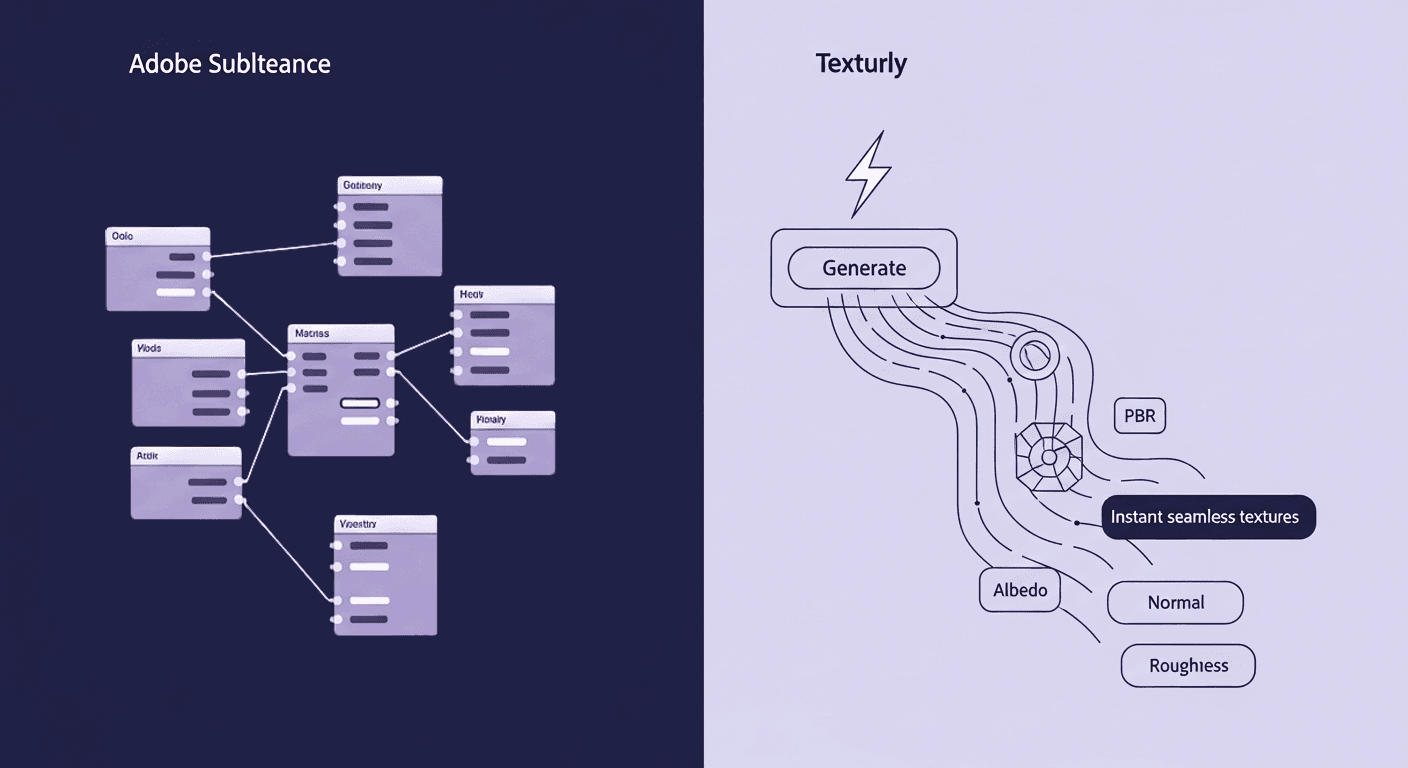

When to Ditch Nodes for AI: A Texturly vs. Adobe Substance Workfl...

AI in 3D design

Texture creation

Mira Kapoor

Dec 22, 2025

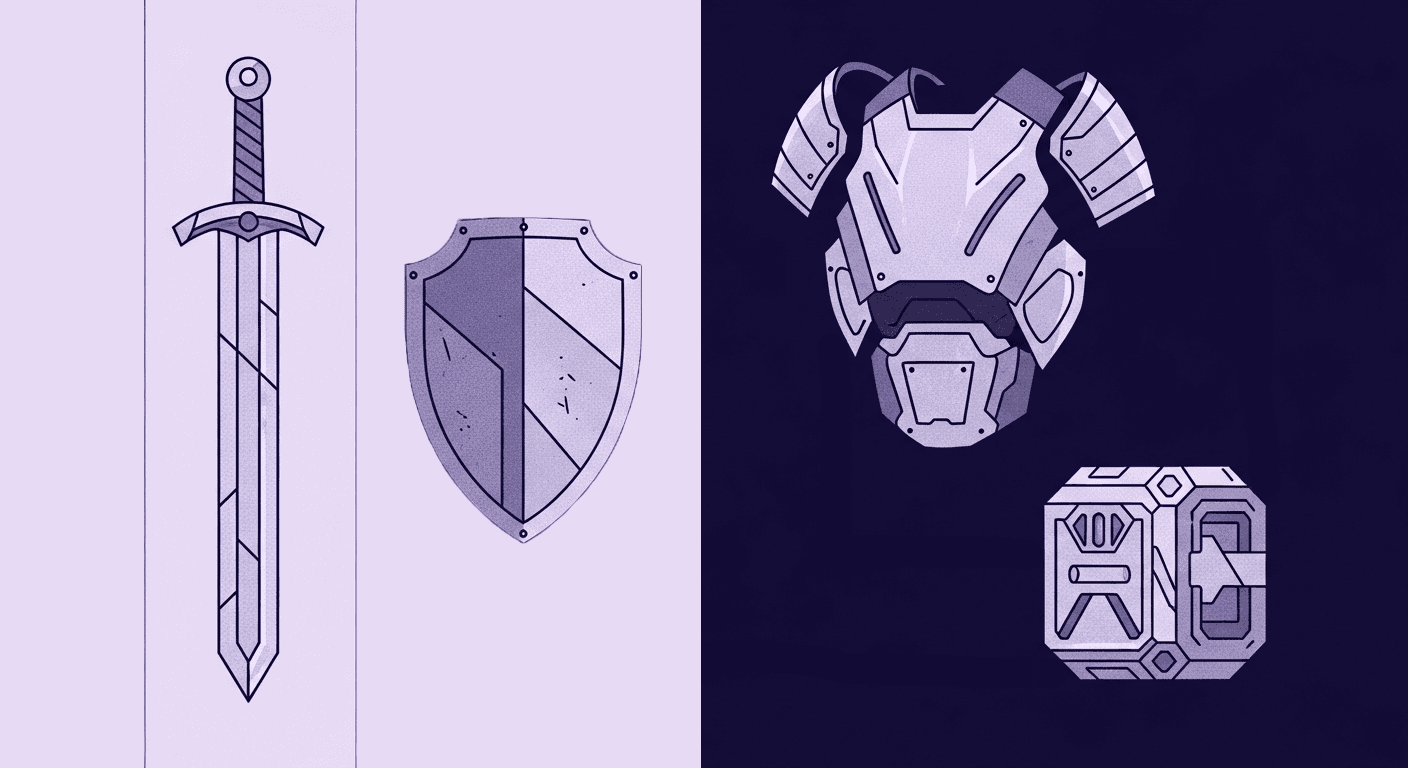

From Dull to Dynamic: The Art and Science of Metal Textures in Ga...

PBR textures

Game textures

Max Calder

Dec 17, 2025